In this final post of my 3-part series on Digital Accessibility, I close by contending that the future of accessibility is here – and it’s time to get on board. In Part 1, I asserted that digital access was a human right requiring our protection. I laid out a strong business case in Part 2 that studied the economic benefits of accessibility. Here, I conclude with one final argument and declare that the future of accessibility is now.

Accessible Innovations Benefit All

“Necessity,” the saying goes, “is the mother of invention.” In other words, when a user’s wants and desires becomes a necessity, product builders need to come up with innovative ways to meet the new demand.

Once in a while, as Dr. Timothy Clark commented in a recent Product Momentum Podcast episode, innovation can be “a lightbulb moment of lone genius.

“But most of the time,” he added, “innovation is the result of a collaborative enterprise, with teams of talented individuals working together and pursuing new ideas.”

I absolutely agree; however, it is difficult to discover new ideas while peering through the cloudy lens of old biases.

Accessible design offers a different view, one that strives to be free of ableism – a continuous pursuit. It allows the active participation of diverse people who bring diverse experiences to the discussion. Their wide and varied experiences introduce new perspectives and new ways to examine old problems.

Take the latest assistive technologies, many of which were initially created to support people with disabilities or other temporary impairments. Many of these innovations have become wildly popular across all segments of society. What’s amazing about the notion of designing for accessibility is that the innovative outcomes become welcome technological advances for all to enjoy. For example –

- Automobile navigation systems work seamlessly with speech-to-text and text-to-speech technologies. Originally created for people with motor disabilities and visual impairments, we all now enjoy access to a far safer hands-free navigation experience, thanks to this innovation.

- The popular Segway has become international phenomenon. Again, the Segway was initially conceived as a reconversion of the gyroscope-based wheelchair, created by Dean Kamen. And now, it is used as a personal transport for commuters and tourists – even for law enforcement on patrol.

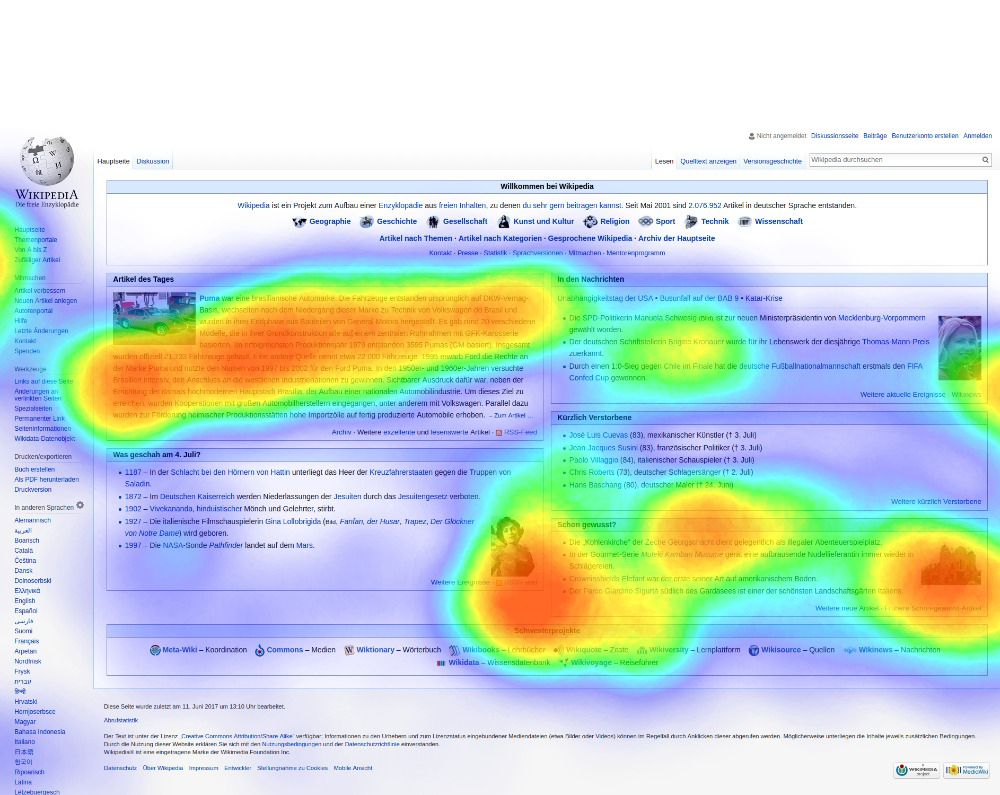

- Eyegaze technology was developed to allow people with advanced motor disabilities navigate using just their eyes. More recently, though, marketers and software designers use Eyegaze to create the “heat maps” that track user attention on-line to better understand how people use their products.

Other examples of assistive technologies include voice-activation tools such as Alexa, Siri, and Google devices. Imagine how a simple innovation like your cell phone’s “vibrate mode” helps the deaf and hearing impaired.

Consider this: nearly 60% of the internet is written in English (source: Visual Capitalist, March 2021). Great news if you can read and speak the language. But if not, it means that 40% of the web is inaccessible – unless you’re fluent in multiple languages. Browser translators open the web to the rest of us, and in the process is shrinking our world.

Necessity may be the mother of invention; but an accessible design mindset converts those inventions into exciting new applications that serve us all.

The Scalability & Compatibility argument

Consumers discover accessibility’s presence (or absence) in their first engagement with the interface. And while user interaction may begin there, the many technical decisions that support a product’s features and functionality begin long before.

Accessibility is about the underlying strength of your digital product’s architecture, which sets the table for what and how you build – both now and later.

While many aspects of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) provide technical accommodations for users’ disabilities, its construction is not alien to the basic protocols of all technologies. The WCAG’s accommodations leverage the infrastructure’s logic and the visual arrangement of information to meet technology protocols that are built by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The W3C, by the way, is the same international community that developed and maintains the WCAG. All new technologies are created based on these protocols.

NOTE: New technologies leverage the same infrastructure protocols as the WCAG. And product infrastructure that supports accessible design aligns with the accommodations initially conceived by W3C.

That’s one reason why an accessible product is also more easily scalable. If you believe as I do that digital tools are living, breathing assets, then you’ll recommend that your architects and developers apply the right coding standards at the outset. In this way, your digital product will be light years ahead in laying the necessary foundation not only to support today’s assistive technologies but also tomorrow’s innovations that have not yet been conceived.

When we create products and websites that protect accessibility, and when we respect WCAG and proper coding standards, we’re embedding legacy directly into them. Technologies evolve; and your code needs to enable and support that evolution.

Closing Argument

Protecting Digital Access: Balancing the Power and Responsibility

The adage, “With great power comes great responsibility” applies as much today as it did in ancient Greece.

As builders of digital products, we enjoy an immense privilege. We also bear considerable responsibility to our products. We are charged with creating digital realties for all – ourselves included – through the products we build. That’s the unspoken understanding, at least.

Perhaps it’s time to question this assumption and ask, “Are my practices including or excluding people?”

In spite of overwhelming evidence, disputes against digital accessibility persist. But as I have outlined in this blog series, they pale in the shadow of the arguments supporting this fundamental right.

As an Accessibility Professional and human rights activist, I find it difficult to explain or convince individuals, businesses, and government leaders why they should adopt accessibility without stating the “you should do your work without violating a basic Human Right” argument first and last.

I am also a person without permanent disability who was born into a world and a culture that ignores (inadvertently and otherwise) the fact that our daily decisions contribute sometimes to the exclusion of several groups. In fact, I recall the day I acquired this knowledge and realized that I would never perceive the world as I once did.

So, while there’s a strong business case to make for accessibility implementation, there’s a more powerful argument that as architects, developers, designers we must abide. In our role as product builders, as creators of the digital world, we are also protectors of human rights in it. Creating accessible products within accessible environments allows more diverse people with different kinds of disabilities and impairments to play an active role in inhabiting and building the digital world of the future.

In some small way, I hope this series helps you consider your own journey on a path to accessibility for all.

ACCESSIBILITY FOR ALL, BUILT FROM THE GROUND UP

ITX architects and developers build software from the ground up to ensure its functionality, accessibility, compliance, and security.

Susana Pallero is a CPACC-certified Accessibility Solutions Specialist. She is also Subject Matter Expert at the International Association of Accessibility Professionals (IAAP) and Collaborating member of the Silver Task Force Community at the W3C. She applies accessibility principles to the most diverse environments and tasks.