Set objective, behavior-based, metrics for both individual and team competence to keep everyone growing.

One day, I had a good friend call my cell and say, “I need a team that can pick up the pieces from another vendor. I need help getting these small features out the door in three months or I’m going to lose my job. Can you help me?” For context, the teams I work with have been building software products for two and a half decades and this has happened on more than a few occasions. This time, my team had worked on this technology platform before, and, represented confidently that they would be able to knock the project “out of the park.” Everyone on my team expressed confidence that this was a no-brainer. You might guess where this is going next.

We did not deliver. Not even close. I will spare you the details of my friend’s professional fate, but it was not a good result. The problem, as I see it, wasn’t malicious intent. No one on my team was lying about their perception of their skills. We asked good questions. We even probed deeply into the causes of the prior vendor’s failure. We thought we had done a thorough assessment of the current state of the system. The team authentically believed that it would be easy. The raw subjectivity that comes along with this territory makes it difficult to lead well. Additionally, the business of building software products is a competitive, high-pressure environment and the incentives are often organized to inadvertently pit vendors against clients.

We would have been able to successfully build the features and save this friend’s tail if we had been more objective about our assessment of our skills. We would have had a much better chance of filling the competence gaps.

On teams where skills are objectively measured, confidence soars, and teams thrive.

When team skills are objectively assessed, they naturally have more confidence in each other and in the team as a unit. I served on an aircraft carrier during the first Persian Gulf conflict, worked on F-14 Tomcats, and got a close look at how skills are assessed in this high-stakes environment. Three decades ago, when I served, this was something that the Navy did really well. There were rigid and obsessively objective standards for knowledge and skills. You had to pass tests and demonstrate your competence, have it checked and double-checked, multiple times in order to move up in rank. There were many sets of eyes on your demonstrated level of competence. It was an expensive process to manage, but given the life-or-death consequences of the work, it was necessary and it worked well. An aircraft carrier is one of the most complex feats of human engineering ever accomplished. The amount of human coordination is astounding.

In the modern VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, & Ambiguity) business world, many of the skills our teams need to innovate are hard to come by or don’t exist yet. Objectively determining competence under ever-changing circumstances is very hard to do. In many cases, by the time you work up a way to test people effectively, you have to change the test. In addition, it is often the people skills that are more valuable than the hard skills. These skills are often context-dependent and can be really hard to measure with a standardized testing instrument. However, all skills can be observed and demonstrated in the wild.

It is imperative for teams to know where they are, objectively, in order to predict success with any degree of accuracy. Unfortunately, we have blind spots. We often tell ourselves stories and create a sense of false confidence that leads to uncomfortable situations. Let’s explore where these come from.

Blind Spots And Fallacies

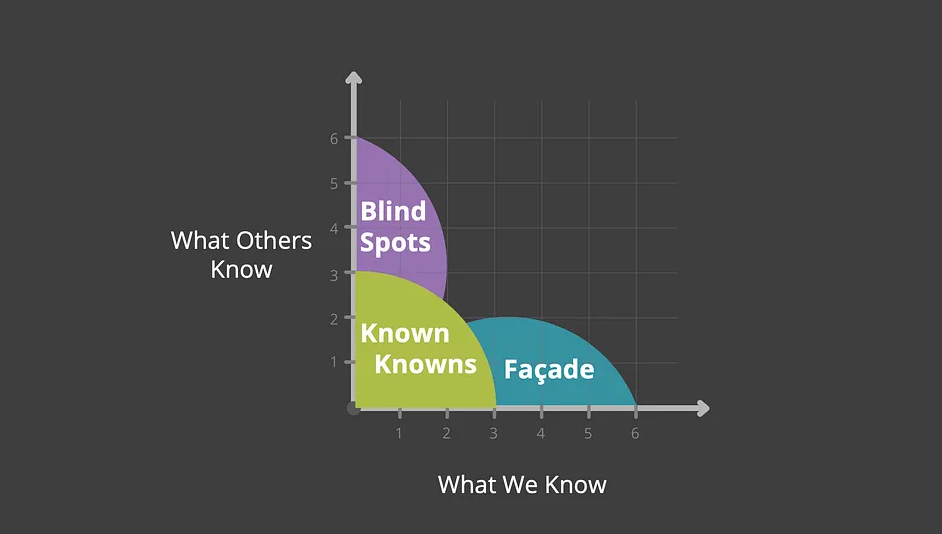

One way to think about our perceived competence is to plot on a graph what we believe others know vs. what we believe we know. In 1955, two psychologists, Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingram described this phenomenon as the “Johari Window”. The model helps people better understand their relationship with what they know and what they don’t know. The model can also be extended in the context of competence for a team, an organization, or a group of people. Near the origin are the things that we believe to have a solid, measurable understanding of. These are the things that are well-known by both our team and others outside of our group. This is the arena in which we compete and is represented by the green area in the graph below. These are our known, knowns.

We also have areas we don’t know: our blind spots. Think of our blind spots as those things we believe others know that we do not. We might know they are out there, but we have not yet mastered the things in this domain. This is represented by the purple area in the diagram above. In the bottom-right portion of the chart are the things we think we know, that others do not. This region is labeled as the façade because we too often overestimate the knowledge and skills of our teams and what we think we know. Our egos sometimes work hard to defend this region. It is safer to assume that others possess the knowledge in question so that we keep an open mind and a growth mindset.

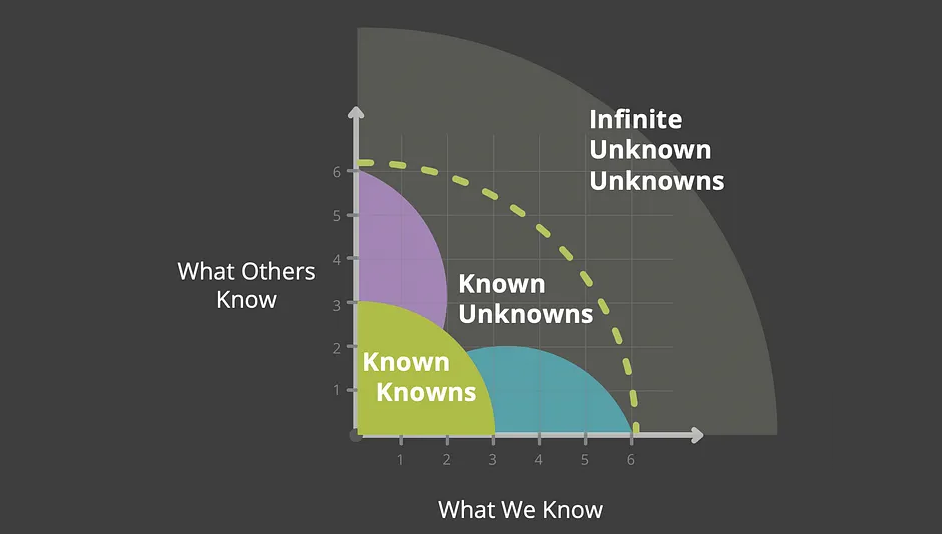

The next two regions that are important to understand in this chart are the known unknown region, beneath the green dashed line, and the near-infinite unknown unknowns region. Thinking in this way keeps us focused on building and planning for adaptability so that we don’t get pigeonholed by an unpredictable event in our unknown future. Authentic and meaningful competence — i.e., building our stock of known knowns — is how we achieve adaptability and agility as an organization. Based on what we and others know, we can attain the confidence to experiment with other pathways to success. On complex problems, the pathways have to be invented. Teams stay motivated by keeping their eye on the mission without getting paralyzed by the complexities lying in the way. It takes meaningful competence to turn our chaos into more predictable progress.

Meaningful Competence

Creating an adaptable organization relies on building tiers of competence in your team. The more complicated the work you do, the more important it is to work on improving the competence of the people working on it. The ability to build systems that build competence in people will be a competitive advantage for your organization. When your team members are learning new skills and they attribute that to their work, they enjoy their work more and spend more time in “flow.” This will have real economic value in the short term, measured by the quality of the work that gets done improves and in your team retention metrics. In the long term, it will ensure that your organization remains adaptable. In most domains, a group of people building competence is exponentially more valuable for the ecosystem than any single person achieving that competence. Some exceptions to this might be domains that value individual contributions over the needs of the organization, like purely artistic endeavors or pure research and development organizations.

People who grow, learn, and contribute to a meaningful goal are more intrinsically motivated and thus, more creative. The role of competence in any human ecosystem is crucial to understanding and evolving. In the handbook of Self Determination Theory, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan describe competence as the difference between “I think” and “I know.” When you have meaningful competence, you can apply it to accomplish a shared goal from the perspective of others. It is only when others, either colleagues or some objective third party whose concerns you are meeting, agree that we have accomplished something, can we objectively claim some level of competence. If you accomplish something, but it doesn’t add value to the ecosystem, it is not meaningful to the ecosystem. Likewise, if no one else agrees that you are capable, it is not yet reliable and therefore, not yet meaningful competence.

Conscious Competence

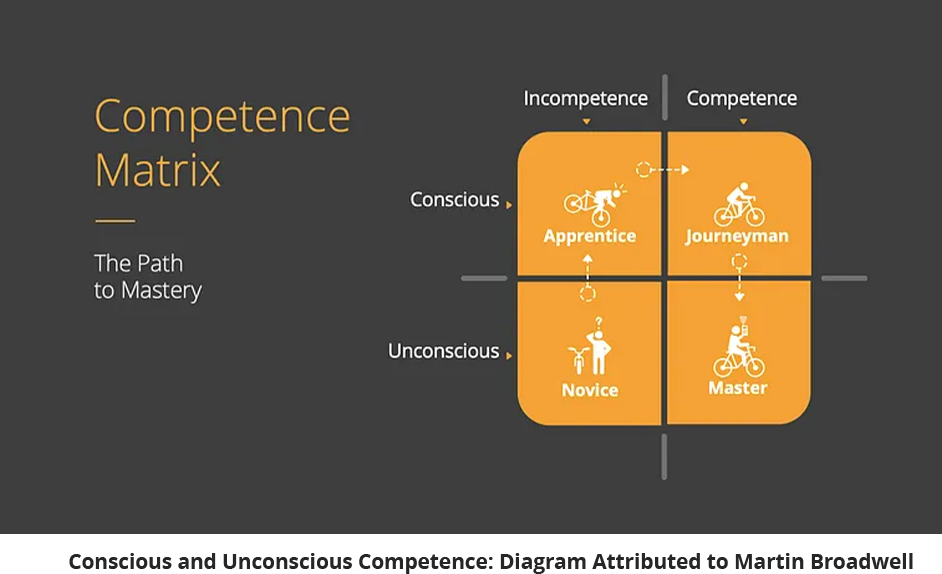

Another of my favorite age-old frameworks for understanding how mastery works is Martin Broadwell’s framework for learning. He claims that we start as novices — assuming we see knowledge we want to acquire. We consciously learn as we practice. Over time, we build habits and patterns into our way of working or being until we master that knowledge — an “unconscious competence” occurs for us. We move clockwise around the diagram, beginning in the lower left quadrant and ending in the bottom right quadrant of mastery. Mastery of any domain takes time to learn and, in most cases, someone to observe and learn from.

Authentic Competence

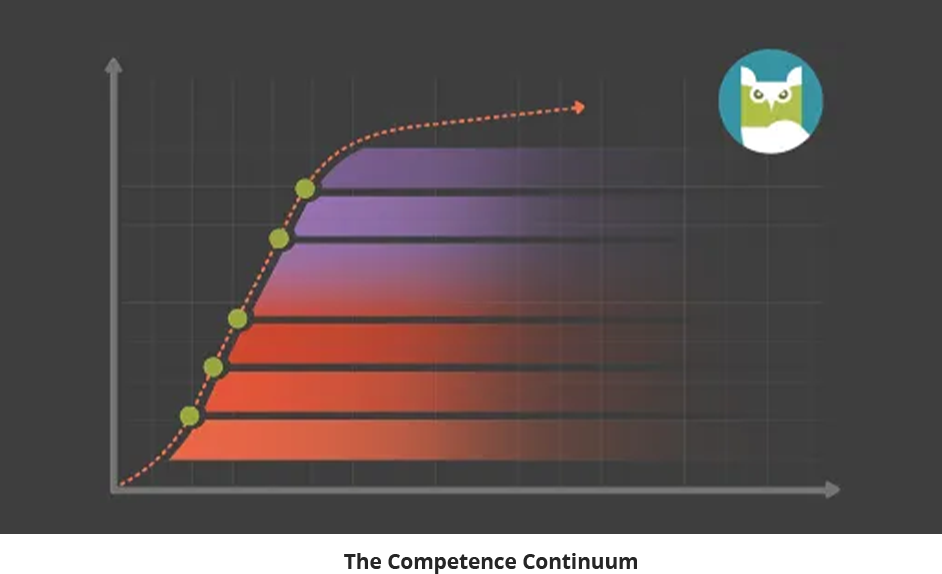

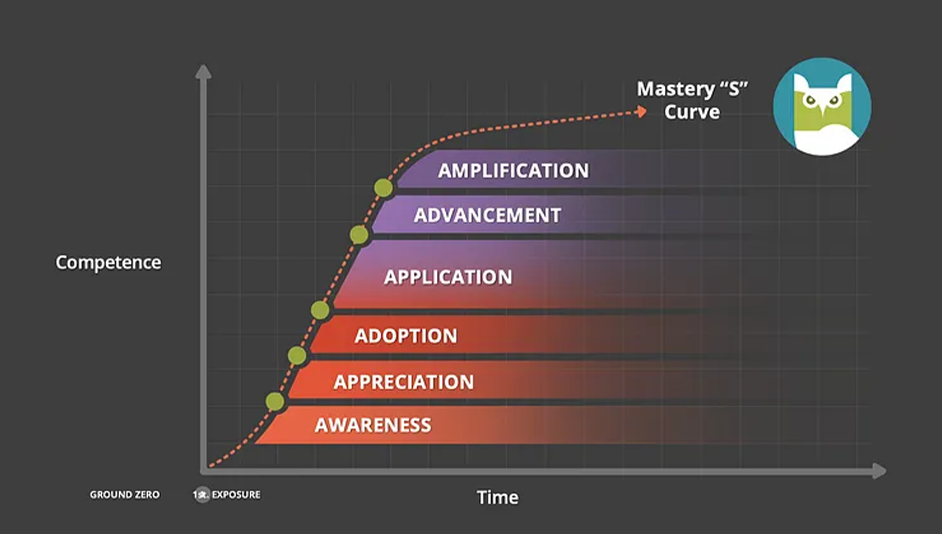

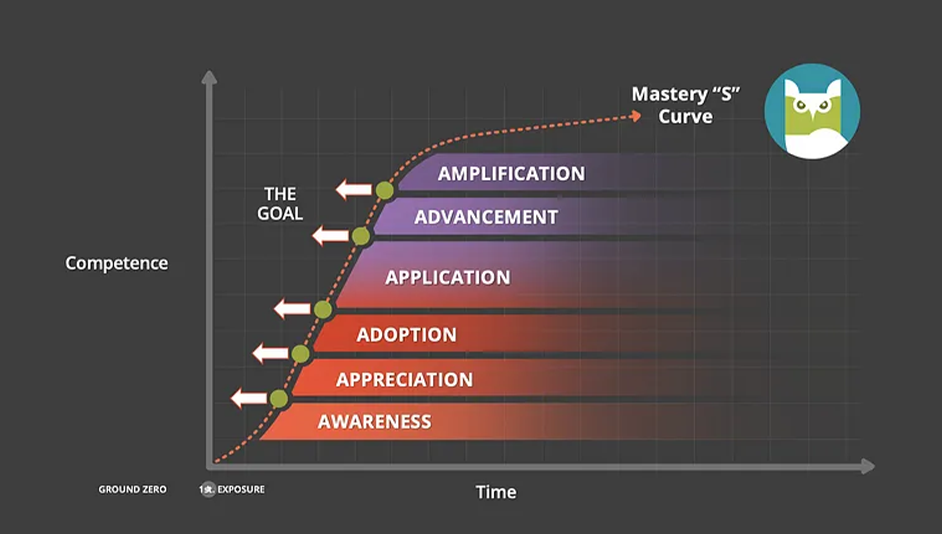

Competence appears more like an “S-curve” of learning for organizations. The Competence Continuum, shown below, is an attempt to integrate previous models about how people learn in a way that allows us to deconstruct knowledge. As a result, we can support the learning process and shift the entire curve to the left, allowing our teams to gain competence faster.

As you progress along the continuum toward mastery, you can break mastery up into six, measurable stages. Each stage has an important threshold that allows you to measure whether or not it has been objectively achieved. When those criteria are met, it demonstrates the achievement of the corresponding level of competence. I call this the competence continuum.

Ground zero (Awareness) shows the point at which you are first exposed to the domain of knowledge. Each stage of learning takes time. After you achieve “mastery,” you realize that the line continues into infinity. There are always next-level “unknown-unknowns” to conquer.

Let’s talk about the six stages. I used an alliteration with “A’s” to make it more memorable:

Awareness. Achieving awareness exposes the learner to language that provides access to the basic concepts, facts, and content. This allows the learner to begin building a sense of familiarity, and they soon become conscious of the fact that they are incompetent in the domain. This is the beginning of their journey. At this stage, it is critical to the consumer’s mindset to make them aware that the domain of competence is both accessible and achievable. For example, if you want to move the needle on “diversity and inclusion” in the workplace, building competence in your team around what “diversity and inclusion” means is a key foundational step. You have to first expose them to the concepts and the language that surrounds diversity and inclusion. They have to be aware that the problem exists, and they have to believe that they can do something about it to consider learning more about it.

The Appreciation Threshold: the point at which learners determine that they care about this domain of competence enough to try to understand and learn more about it. This demonstrates that they are ready to take the next step. You might measure that they have reached this stage because they have made a time commitment to look into it.

Appreciation. At this stage, the learners understand the basic concept exists. But the learners have not yet put what they’ve learned into action yet. They don’t actively use the information to make decisions because they have not yet connected to the purpose and have not yet decided to adopt it. Our job as leaders is to connect learners to the purpose of the knowledge or skill. We need to inspire them to want to learn it. Another key to the appreciation phase is the growth mindset. The learner has to believe that they can attain the skill or knowledge. If they enter this phase with a fixed mindset, they are doomed to fail. That’s because people don’t learn linearly. As they consciously practice, they will make mistakes on their way to conscious competence.

The Adoption Threshold: learners cross the “Adoption Threshold” when they self-determine that they care enough about this domain of competence to incorporate it into their lives and adapt their behavior to gain knowledge or skills through learning and practice. You might measure that they have reached this stage because someone else has observed them accomplishing it or utilizing the knowledge in the wild.

How to Objectively Measure Appreciation:

- Has a stated or written, SMART goal for learning the thing.

- Has demonstrated progress toward learning the thing.

Adoption. The magic really starts when we recall the information or content at the appropriate times without external triggers. This is competence in action. We can put the knowledge to work to make decisions and, as a result, our personal behavior changes. We have made the knowledge our own. We do things right and we actively learn the language or skills required to adapt and adopt behaviors and knowledge, as well as assimilate the competence into our work and our lives.

The Application Threshold: learners cross the “Application Threshold” when they demonstrate that they have learned the skills or gained the necessary knowledge. You might measure that they have reached this stage because multiple people have observed and provided feedback on them accomplishing it or utilizing the competence in the wild.

How to Objectively Measure Adoption:

- Recognized by their peers as having successfully done the thing at least once.

- Recognized externally as having successfully done the thing.

- Recognized by an externally validated third party, like a certification.

Application. Mastery only comes with practice and time. This is the origin of the 10,000 rule of mastery in any domain. The rote application of a skillset over a period of time, in the arena, is where authentic confidence is built. This is the point at which the learner has demonstrated many times that they are able to apply the knowledge or skill consistently. In this phase, the learner actively stays in the “zone” of learning and improving different nuances of knowledge or skill. They recognize when they have mastered part of the domain and are growing bored and they seek out new learning. Alternatively, they recognize where their knowledge or skill gaps are causing them frustration and put their heads down to overcome the challenges at hand.

The Advancement Threshold: when a learner puts their personal seal of approval on the content, shares concepts they have learned in conversations with others, and learns to teach the concepts, they begin to help spread awareness. At this point, they have crossed the “Advancement Threshold.” You might measure that they have reached this stage because multiple people have provided feedback that they taught or purposefully exposed others to the domain in the wild.

How to Objectively Measure Application:

- Recognized by their peers as having successfully done the thing multiple times.

- Recognized externally as having successfully done the thing multiple times.

- Acknowledge as reliably capable of doing the thing by others.

Advancement. This is a high form of engagement with knowledge. It occurs when learners initiate conversations with others in the context of the knowledge to move the needle on performance. This is where you start to build competence in a community or people. When we have engaged others and created an impact beyond ourselves, we have gained momentum within the context of the ideas and are turning them into wisdom through sharing. It is in this phase that the consumer of knowledge turns into a teacher and sharer of that domain of knowledge.

The Amplification Threshold: When your community begins to experiment with new ways of executing, training, or improving the value delivered in the domain, they have crossed the “Amplification Threshold.” When they care enough about the domain to reach for an even better result and work to improve the domain, this is a powerful form of mastery. You might measure that they have reached this stage because they have been recognized by their peers or by the outside for their contributions to the domain.

How to Objectively Measure Advancement:

- Recognized by their peers as having trained others in the domain.

- Recognized externally as having demonstrated proficiency in the domain.

- Demonstrated evangelism of the knowledge.

Amplification. Momentum occurs when we work to improve the domain of knowledge through thoughtful experimentation. Some of these experiments result in innovations that improve the performance of the system. This is the evolution of competence. When we have engaged others and have worked to improve the domain for others, we have gone beyond what is expected and are creating ways to accelerate the learning and the craft. At this stage, we experiment with ways to improve access to the ideas, advance the ideas, and take the skills to higher levels. The amplification stage is the holy grail for competence-building in any domain. Our goal should be to maximize the number of people in our ecosystem that reach this stage. Our longer-term goal is to collapse the timeline in which competence is achieved, moving the curve to the left.

How to Objectively Measure Amplification:

- Recognized by their peers as having advanced the domain by teaching better practices.

- Recognized through an award or third-party acknowledgment of accomplishment.

- Confirmed contribution to training materials or process documentation.

These levels can be put into a matrix or a spreadsheet to show where each member of your team is with respect to their objective level of competence. You can then roll your skillsets up to give you a view of your organizational competence.

I have seen too many instances of “competence surveys” that lead to inauthentic conversations and bruised egos. Attempts to assess competence that are based on subjective surveys are better than nothing, but an objective, observation-based, and validated approach is much more meaningful for your organization, will breed confidence, and will reduce organizational politics and posturing.

Confidence and Overconfidence

I have met many business leaders and entrepreneurs in my travels and career. The successful ones are those who know how to ride this line of competence and confidence masterfully. Leaders offer a bold vision of the future — even if the leader isn’t sure that this vision is perfect. The team will build its competence — and everyone’s confidence — as they learn and create to achieve the vision. A proper vision and an environment where people can safely experiment, grow, and learn, can lead to unbelievable accomplishments.

On the other hand, I have seen dramatic failures when overconfidence is taken to the extreme and teams are sent on death marches with no chance of success. This is often because their leaders are either not aware of their confidence levels or not focused on powerfully growing their people and teams along the way. It is important to keep a finger on the pulse of your team so you can ride the line and support their confidence without them becoming overconfident.

When leaders understand their blind spots, they can plan to learn and refine their vision of the future, based on the teams’ deliverables. When teams understand their own blind spots, they can see what else they need to learn. The more transparency and objectivity we create around competency levels, the more our teams can achieve over time, as they learn. Progress and success rely on having proven competence, a growth mindset, and the confidence to create an environment that allows our teams to learn and achieve even more.

If you liked this, clap, share widely, and let me know how it works for you. I promise to honor your feedback.

References:

Objective Prioritization is Impossible, Sean Flaherty (2019).

Flow, Czikszentmihalyy, Mihaly (2008).

Blink, Malcolm Gladwell (2005).

Insanely Simple, Segall, Ken (2012) (Note: In his story about Steve Jobs, he describes the “Reality Distortion Field” created by Jobs that people were able to step into to create products that didn’t exist before.).

Teaching for learning (XVI), Broadwell, Martin M. (1969).

“The Johari window, a graphic model of interpersonal awareness,” Luft, J.; Ingham, H. (1955).

Proceedings of the Western Training Laboratory in Group Development. (Note: This is a graphic model of interpersonal awareness. I am extending it to groups in this article).

Mindset, Carol Dweck (2006).

The Handbook of Self Determination Theory, Ed Deci and Richard Ryan (2004).

Sean Flaherty is Executive Vice President of Innovation at ITX, where he leads a passionate group of product specialists and technologists to solve client challenges. Developer of The Momentum Framework, Sean is also a prolific writer and award-winning speaker discussing the subjects of empathy, innovation, and leadership.